System Systems

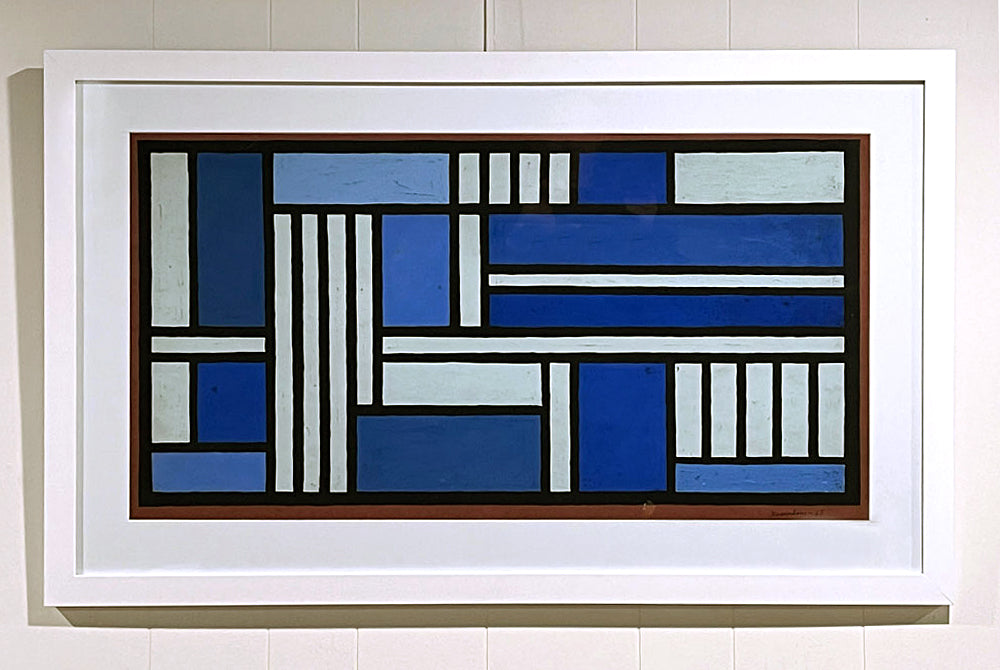

Early Cubist Abstract 1948 Chicago Artist Rudolph Weisenborn MCM Modernism (White)

Early Cubist Abstract 1948 Chicago Artist Rudolph Weisenborn MCM Modernism (White)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

This is an early 20th century modern abstract, cubist style painting by Rudolph Weisenborn. At this time Weisenborn was an active artist and teacher in Chicago. This piece demonstrates his style quite well, a wonderful cubist, modern composition in blues. The current orientation of this piece could also be hung vertically, the signature is signed on the horizontal and this is currently set up to hang horizontal. Either orientation could be done depending on your wall space.

About the Artist:

Rudolph Weisenborn Born in Chicago to German parents and orphaned at age nine, Rudolph Weisenborn led a peripatetic life during his youth before settling in Colorado, where he worked as a cowboy and gold miner. In Denver, he enrolled in the Students’ School of Art and studied there for four years under Henry Reed and Jean Mannheim, a German-born, French-trained artist.

Weisenborn followed a traditional academic curriculum, drawing from casts for two years before working with live models. Even as a young artist, he rebelled against the strictures of what he believed to be a stifling approach to art, stating, “It took me ten years to get it out of my system.”

Weisenborn thrived in the lively artistic environment in Chicago in the early decades of the twentieth century. Encounters with the proto-cubist work of French artist Paul Cézanne and other avant-garde artists spoke to Weisenborn’s “language of the modern world and its new vision.” His portraits, landscapes, and cityscapes from the 1920s and 1930s reflect a thoughtful synthesis of his “own experiments, visions, [and] feelings” with a modernist vocabulary drawn from Cubism, Futurism, Vorticism, and Expressionism. Weisenborn was deeply committed to moving beyond naturalistic representation, declaring that “the motivation is abstract, the result is abstract.” His large-scale canvas Chicago (1928, Illinois State Museum) manifests the artist’s intent to create “a vital organization instead of a static composition” in his abstractions. Credited as the first abstract painting to be shown at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1928, Chicago generated ample press coverage and was a considerable sensation.

For more than thirty years Weisenborn’s paintings, drawings, and prints continued to generate a lively dialogue among artists, viewers, and critics about abstraction, modernism, and artistic experimentation. He participated in numerous group and solo exhibitions, showing frequently at Chicago venues from 1914 to 1965 including the Art Institute of Chicago (from 1918 to 1949 and again in 1965), the Salon des Refusés, the Renaissance Society, and the No-Jury Society of Artists, as well as in New York, Albuquerque, and other cities. During the Depression, Weisenborn executed several murals for the Works Progress Administration, including a series at Crane Technical High School and a Cubist-inspired mural at Nettlehorst Elementary School in Chicago. In 1933 he contributed the only nonobjective painting shown at Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition.